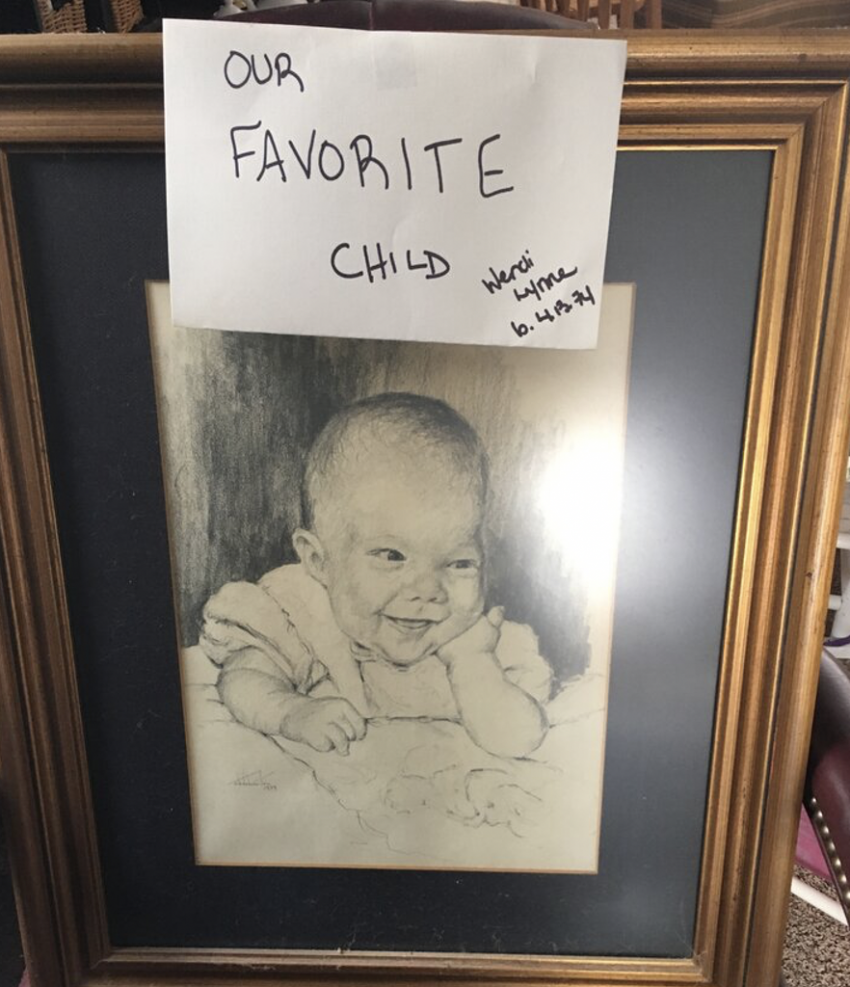

I’d like to take you back. Back to the roughly four days of warmth and sunshine between Willie’s illness and Indy’s Parkinson’s. They were gone in a blink, those days. It took me a year and a half to bring Willie out of illness. Almost as soon as it was over, I started another year and a half journey bringing Indy into illness.

Things had just begun to calm down after Willie’s abrupt and prolonged hospitalization. The eighteen-month slog hadn’t made Willie 100%, but she was close enough. Had her illness been a traffic jam, this is when the police would have started waving everyone through.

I say she wasn’t 100% because Willie’s memory – which hadn’t been great before the sepsis – was a bit worse in the aftermath. It’s the little things Willie doesn’t recall, like when Indy gives her phone messages she later insists he never gave her.

Willie uses her failed recollection as confirmation she never had the information in the first place.

How do you argue with that?

Take Christmas 2016, thirteen months after Willie was discharged from the hospital. She had insisted on hosting the family holiday party. I, concerned it may be too much work, had offered to handle a few things on her party to-do list. One task I took over was buying the wine.

I told Willie I planned on hitting my favorite vineyard for their signature labels – Diego Red and Concordia, two reds with perfect composition. Neither is as heavy as a traditional red, nor as bubbly in texture as a rose. Niagara, their white, isn’t sweet or overly dry like some whites. And their Blackberry sounds far more saccharine than it tastes.

Willie and I haggled a bit over the wine. She wanted more traditional wines, not the Gen X-er nonsense I planned on buying. She wanted merlot. Chardonnay. Maybe a pinot noir. Finally, with Willie’s list in hand, I headed for the winery.

Let’s just say I wasn’t only making purchases for the holiday party.

The day of the party, I wended my way through my parents’ house, lugging my case of wine to the back foyer, where Willie had set up a makeshift bar. Bottles of wine were already laid out for the partygoers. A merlot. A chardonnay. A pinot noir.

Infuriating. Why had I gone to the time and trouble of buying wine when Willie was just going to buy her own? I mean, yes, I had restocked my own supply while I was at the vineyard. The staff there had stopped asking me months ago if all the cases of wine I bought were for parties.

But that was hardly the point. Willie’s memory was like a fishing net; able to hold most of the catch, but not all. The fish escaping through the openings in the net were her recollections, seeking life elsewhere. And here it was. Ruining my life. Again.

That’s maybe a touch dramatic. Willie’s fishing-net memory was sending me on errands I was running away?

Nah. I’ll stick with the dramatic.

Ignoring the fact 73-year-old, post-sepsis, fishing net-brained Willie was trying to host a party, I stalked into the kitchen, demanding to know why Willie had procured her own wine.

“Don’t you remember?” Willie asked, as though I was the one with the fishing-net memory.

Through gritted teeth, I assured Willie yes, I remembered our conversation.

“So yeah,” Willie said, “you were going to buy the different stuff. The blackberry or whatever. And I was going to buy the regular stuff.”

But that’s not how our conversation had gone. Willie had been unsure of the Concordia and the Niagara, with their weird names and weirder flavor profiles. I told her my vineyard had regular stuff too. Pinots and whatnot. We agreed I’d get those.

“No,” Willie answered. “I told you to get the other stuff. It sounded good. But that I’d have regular stuff too.”

Which I knew was dead wrong because A) had Willie said she was still going for wine I would have put up a fight and B) Willie doesn’t compliment anything I do, least of all my drinking.

I returned to the foyer to unpack my now-superfluous wine. I cursed the fact I didn’t have my Concordia here to drown my angst. Just some stupid merlot and Yeungling Light.

Not even regular Yeungling. Yeungling Light. Light! I mean, I’m sorry. I didn’t realize this was a junior high party. Are we going to talk about boys? Slather on Lip Smackers? Stay up all night?

I pulled my bottles of wine from the case.

A few Concordias. Some Diego Reds. Two Niagaras. A not-too-sweet Blackberry.

What the hell? I couldn’t be the one incorrectly recollecting our conversation! I don’t get things wrong. Ever. Do you know how hard that is? Why do I work this hard to always be right, only to get the wine wrong?

No chance was I telling Willie. Willie would use it as proof it wasn’t her memory that had a problem. I couldn’t have that.

Plus it was Christmas. I’m not going to admit fault at Christmas.

So obviously. You can see how Willie’s memory had been a problem since her illness. By the time we were a year and a half out, it was clear that would remain her only sequela from her sepsis. I had done all I could. I could see the end of the traffic jam. I was almost to the open road.

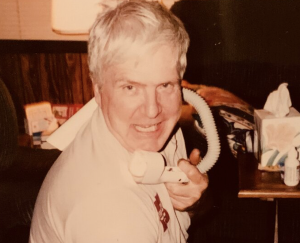

That’s when Indy’s left hand began to shake.

His doctor wanted him to see a neurologist. My territory. I asked Indy questions, trying to glean more information. And as everything he told me fell in line with Parkinson’s, the traffic began to close in again.

I didn’t tell Don, not right away. He was about to head out on a ten-day fishing trip. A trip so remote he’d have no communication with the outside world.

I mean, whatever floats your boat there, fella. No internet? No thank you.

He’d worry, and I didn’t want him to worry. When I did tell him, he pointed out I was on step 646, but my dad was still at step one. Less than that, really. He hadn’t even been to neurology yet.

Well, I knew what I knew, and I’m never wrong.

I mean, yes, there was the wine. But I think Willie switched it out somehow. You know, to trick me into thinking I was the one with memory problems. There’s no way I got that conversation about the wine wrong.

Think about it. All she had to do was intuit when I bought the wine. Then she had to go buy the Concordia and everything, which is only sold at that vineyard, deep in Bucks County where Willie has never been. She would have bought that Concordia and its compatriots, using the list of my planned purchases, which she of course wrote down during our conversation.

Then, she would have waited for me to leave my house. Though she possesses neither key nor alarm code, she gained access to my house and switched out the wine in a diabolical attempt to get me to end my carping about her memory.

Entirely plausible.

Anyway. Before neurology would see Indy, they wanted an MRI of his head. This had to be ordered by his family doctor. Knowing exactly how the MRI should be ordered – I’ve ordered dozens of them myself, and I’m always right, remember? – I made the phone call, then scheduled the MRI. I couldn’t even schedule an appointment with neurology until I had that MRI report in my hands.

I called Willie with the MRI date and location. Then I packed up for a two-week trip in Wyoming. Our Wyoming house lacked WiFi. Cell service was as erratic as Willie’s memory. But still. The day of the MRI I called Indy to see how it had gone. By the end of the week I’d have a report. Then I could call neurology.

“What MRI?” Indy asked.

Now, Willie maintained she told Indy about the MRI. Indy said not so much. Willie said it didn’t matter anyway. They had a Phillies game that day. The MRI would have made them late for the Phillies. She would have canceled the MRI. There’s no room in Willie’s life for tardiness at Phillies’ games.

You see what poor Willie is dealing with here. A husband thoughtless enough to develop Parkinson’s at the beginning of baseball season? A daughter inconsiderate enough to schedule a much-needed MRI on the same day as a ball game? All while she’s forced into making fiendish plans that gaslight me into thinking I’m the one with the pothole memory?

My entire life’s happiness lay in that MRI. Without the MRI there was no neurologist. Without the neurologist, I couldn’t get a Parkinson’s diagnosis. Without that diagnosis I couldn’t sleep. I exert control by planning. How could I possibly plan until I knew what to plan for?

I also exert control by lying about which wine I brought to Christmas.

Seeking the one spot in the house where cell reception could generously be called good, I spent an hour rescheduling that MRI.

Don’t ask why it took an hour. It just did. Parkinson’s slows everything down.

It would be four months after Indy first told me about his hand before we finally sat at the train station, waiting to ride into Center City to see the neurologist.

Indy is, in medical parlance, a terrible historian. His answers to the same question posed at different times are as varied as the wine at the Christmas party. But I wanted him prepared for the neurologist’s questions. Waiting for the train, I told him what the neurologist would ask. And as Indy answered, he gave responses in complete opposition to those he’d given me four months ago.

Four months of worry dissolved. The traffic cleared again. This sounded far more benign than Parkinson’s. We’d make short work of this neurology appointment. Probably never have to go back.

Two hours later, I sat in the Irish Pub on Walnut Street, slamming back the stout my dad had just bought me. His answers for the neurologist had veered back towards where they’d been four months ago, although it would be another year, four more specialists, and six more tests before we had our Parkinson’s diagnosis.

Which is pretty common in Parkinson’s disease.

Now, in the very near future, I’m going to tell you a story about Willie, Indy, their TV, and an electrician. I’ll need you to remember this tale when I tell you about the electrician.

I’ll also need you to forget I was the one who messed up the wine.

Never happened, right guys?